National Air and Space Museum’s Sikorsky JRS-1: Pearl Harbor Survivor & A Witness To History

Story and photos by Corey Beitler

When its doors open to the public daily, the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, tells the story of aviation and space exploration with over 170 aircraft, 130 space vehicles, and thousands of smaller artifacts on display. Visitors to the museum can admire the sleek lines of the Concorde, the world’s first supersonic commercial airliner, and the massive size of the Space Shuttle Discovery, which flew 39 missions and spent 365 days in space. Also on display is an example of the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird spy plane, the fastest crewed air-breathing jet aircraft ever built. Visitors to the museum can also see an example of the Grumman F-14 Tomcat jet fighter, which gained fame when it was featured prominently in the movie Top Gun, and a Boeing/McDonnell Douglas F/A-18C Hornet once used by the world-famous U.S. Navy “Blue Angels” Flight Demonstration Squadron.

Thousands of smaller artifacts in the museum are just as intriguing, such as a collection of space suits worn by astronauts and a showcase of memorabilia commemorating Charles Lindbergh’s New York-to-Paris flight with the Spirit of St. Louis. Another exhibit features space-themed toys and robots from the 1950s and 1960s. The museum also features dozens of models of famous aircraft professionally built by dedicated modelers.

Of all these incredible pieces of history within the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, one aircraft currently displayed on the museum’s ground floor deserves special attention. The Sikorsky JRS-1 amphibious aircraft on display has certainly seen better days. Some of its fuselage windows are broken, the paint is well-worn and weathered, and panels and fabric are missing on its wings. But this Sikorsky JRS-1 has special importance in the National Air and Space Museum collection because it witnessed history. This aircraft is the only one in the national collection that was present during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. It is also one of only a handful of aircraft that survive in museums or in airworthy condition still in existence that were at Pearl Harbor on one of the darkest days in American history.

The Sikorsky S-43 “Baby Clipper” was an amphibious aircraft designed and built by Sikorsky Aircraft and was designed by the company’s founder, Igor Sikorsky. The S-43 was a smaller version of Sikorsky’s larger S-42 “Clipper”. The S-43 had the benefit of not only having a watertight hull for operations off water surfaces, but also conventional landing gear, allowing it to use normal runways. The main landing gear wheels retracted neatly into the S-43’s hull, reducing drag and improving the aerodynamics of the airframe. The S-43 was marketed toward airlines that served routes in locations where the aircraft’s amphibious qualities would be ideal.

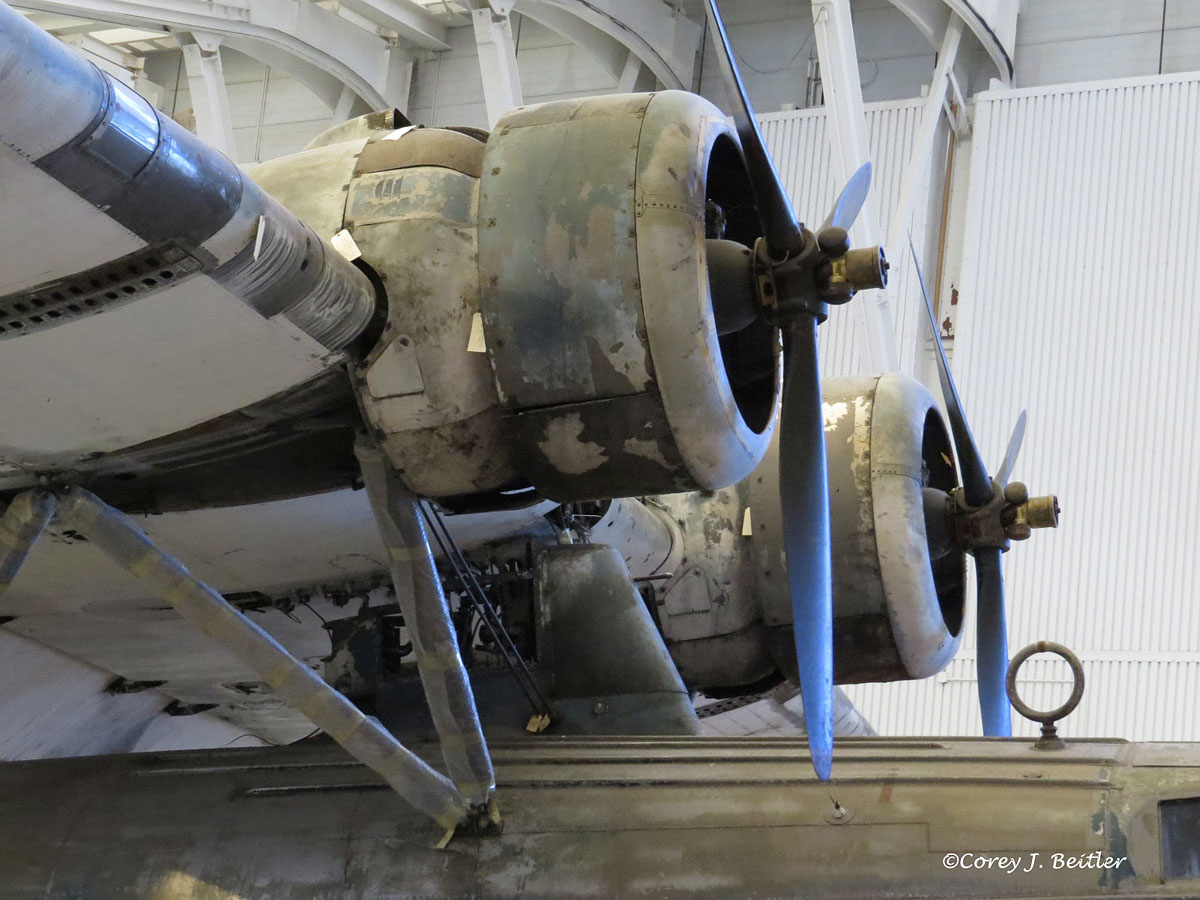

The S-43 was designed to accommodate a flight crew of two, with a position for a radio operator and navigator available behind the cockpit for longer flights where a third crewmember was required. The S-43’s passenger cabin could carry 18 to 25 passengers and had removable seats so that the aircraft could be configured for cargo operations. The S-43 was powered by a pair of Pratt & Whitney R-1690-52 Hornet nine-cylinder, air-cooled, radial engines developing 900 horsepower each. These engines were mounted high on the wing above the fuselage to minimize water spray ingestion. The S-43 had a top speed of 190 miles per hour, cruised at 166 miles per hour, and had a range of 673 nautical miles. Standard operating altitude was 19,000 feet, but in 1936, an S-43 set an altitude record for an amphibious aircraft when pilot Boris Sergievsky flew one to an altitude of 27,950 feet above Sikorsky’s headquarters in Stamford, Connecticut.

The S-43 was built in small numbers and primarily used by Pan American Airways for flights to Cuba within Latin America. Inter-Island Airlines (which rebranded to Hawaiian Airlines in 1941) operated four S-43s to fly passengers from Pan Am Clipper flights, and residents from Honolulu throughout the Hawaiian Islands. The Brazilian airline Panair do Brasil operated seven S-43s. A French company, Aerómaritime, operated five S-43s on a colonial airway between Dakar (Senegal) and Pointe-Noire (Congo) from 1937 to 1945.

The S-43’s usefulness as an amphibious aircraft attracted the interest of the U.S. Navy, which felt it would be useful as a utility aircraft. The U.S. Navy ordered 17 S-43s, designated the JRS-1 in U.S. Navy service, between 1937 and 1939. Except for some minor changes, these aircraft were essentially the same as the civilian S-43. Two JRS-1s built for the U.S. Navy were transferred to the U.S. Marine Corps. The U.S. Army Air Corps also ordered five S-43s, designated the OA-8 in U.S. Army Air Corps service. The OA-8s were used for general utility work at U.S. Army Air Corps bases throughout the United States during the late 1930s and early 1940s.

In U.S. Navy service, most of the JRS-1s built were assigned to Utility Squadron One (VJ-1). Initially based at Naval Air Station San Diego in California, the squadron transferred to Naval Air Station Ford Island at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in 1940. The squadron flew its 10 JRS-1s to Hawaii, with the aircraft fitted with extra fuel tanks in the fuselage so they could make the long flight, which was beyond the normal operating range of the JRS-1.

While stationed at Ford Island, VJ-1 operated in a utility role and was assigned flights that helped keep the U.S. Navy functioning on a daily basis in the Hawaiian Islands. Some of the tasks carried out by the JRS-1s of VJ-1 included towing targets for gunnery practice, aerial photography, and delivering mail, personnel, and other supplies to various military installations on the Hawaiian Islands.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, all 10 JRS-1s stationed at Ford Island survived the attack. The JRS-1s were quickly sent airborne with flight crews in a desperate search to find the Japanese fleet. It was hoped that one of the JRS-1s could locate the Japanese fleet and radio its position back to Pearl Harbor. The JRS-1s searched for over two hours but failed to find the Japanese fleet. In the weeks following the attack, the JRS-1s were used for survey flights to take aerial photographs of the damage to the military installations and naval vessels throughout Pearl Harbor.

The National Air and Space Museum’s JRS-1, construction #4346, was completed by Sikorsky on July 12, 1938. It was the 13th aircraft delivered out of the 17 ordered by the U.S. Navy. Sikorsky officially delivered the JRS-1 to the U.S. Navy on July 28, 1938. The U.S. Navy assigned the aircraft to Utility Squadron One (VJ-1) at Naval Air Station San Diego, California, on August 3, 1938. In 1940, VJ-1 and its JRS-1s transferred from Naval Air Station San Diego to Naval Air Station Ford Island at Pearl Harbor. During its time at Pearl Harbor, this JRS-1 operated in a general utility role with VJ-1.

On December 7, 1941, Ensign Wesley Hoyt Ruth was having breakfast when the Japanese planes began bombing the Pearl Harbor military installations. He immediately got into his car and drove to the north end of the island, seeing the U.S.S. Arizona get bombed and explode while on the way there. After the two surprise attacks on the military installations at Pearl Harbor, over 300 planes and 20 ships were destroyed. Over 2,000 Americans were killed, and more than 1,000 were wounded. The attack forced the United States to enter World War II.

Finally making it to Naval Air Station Ford Island, Ruth climbed into the pilot’s seat of the JRS-1 that is now part of the National Air and Space Museum’s collection. Although not equipped for the mission as they were not fitted with defensive armament, armor-plating, or self-sealing fuel tanks, the JRS-1s were being pressed into service to conduct a frantic search for the Japanese fleet. Along with Ruth in the JRS-1 were a co-pilot, a radio operator, and three sailors. Other JRS-1s were being manned similarly. Just before Ruth took off, a senior officer ran up to the JRS-1 and gave the sailors three rifles. In addition to serving as extra lookouts, the sailors were tasked with defending the aircraft against any Japanese fighter aircraft that might attack them if they found the Japanese fleet. To shoot at any attacking Japanese aircraft, the sailors would have had to shatter the cabin windows or open the cabin door in flight. This would have been a futile effort against fast Japanese fighter aircraft.

In the middle of intense American anti-aircraft fire, Ruth and four other pilots got their JRS-1s airborne and headed out to search for the Japanese fleet. The JRS-1s could only carry depth charges to use against enemy submarines and did not carry any bombs or torpedoes to use against the Japanese ships. The hope was that if any of the JRS-1s found the Japanese ships, they could radio their position back to Pearl Harbor before being shot down by Japanese fighters, so a counter-strike could be launched using U.S. aircraft at Pearl Harbor, and from the U.S. Navy Pacific Fleet aircraft carriers, which were fortunately not at Pearl Harbor at the time of the Japanese attack.

Ruth flew the JRS-1 about 1,000 feet below the clouds so he could duck into the clouds if the Japanese fleet was spotted in the hopes his aircraft wouldn’t be seen. Ruth flew about 250 miles north and then turned east, failing to make contact with the Japanese fleet. What Ruth didn’t know at the time was that the Japanese fleet had turned northwest to recover their aircraft, and he had been within 30 miles of the Japanese ships with his JRS-1.

The next challenge for Ruth and his crew was to return safely to Naval Air Station Ford Island. In anticipation of additional Japanese air attacks, American anti-aircraft defenses were on high alert. Several American aircraft were shot down in friendly fire incidents in the hours after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Despite the danger, Ruth, his crew, and the other JRS-1s returned to Naval Air Station Ford Island without incident.

In the days after the Japanese attack, the JRS-1s of VJ-1 continued to fly patrol missions to search for the Japanese fleet and Japanese submarines that might be lurking off the immediate coast. U.S. Navy ground crews quickly modified the JRS-1s so they could carry small general-purpose bombs in addition to depth charges and mounted defensive machine gun armament on the aircraft for use against enemy fighter aircraft that might attack. The JRS-1s also flew search-and-rescue missions to look for any survivors of the attack that might still be in the water.

A critical task of the JRS-1s of VJ-1 in the weeks following the attack was aerial photography. The JRS-1s and their crews flew dozens of aerial photography survey missions over the Hawaiian Islands. The aerial photography taken by the JRS-1s and their crews helped the U.S. Navy and other branches of the military conduct damage assessments of ships and installations and plan salvage operations. Most of the surviving aerial photographs of the aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the surrounding military installations were taken by the JRS-1s and their crews in the weeks after the attack.

The National Air and Space Museum’s JRS-1 also underwent a paint scheme change following the Japanese attack. Before the attack, the aircraft was painted silver with bright chrome-yellow wings and colorful markings identifying its squadron and role. In the weeks following the attack, U.S. Navy ground crews quickly changed the JRS-1’s color scheme to a blue-gray top coat with light gray undersurfaces. The JRS-1 was painted in this color scheme to provide a measure of camouflage for wartime operations.

The National Air and Space Museum’s JRS-1 was removed from flying patrol and aerial photography work in September 1942. In 1943, the airplane was given a complete overhaul and sent to Moffett Field in California. At Moffett Field, it became the personal aircraft assigned to the commander of Airship Wing 31. The JRS-1 was assigned to this role until August 1944, when it was withdrawn from service and placed into storage with only 1,850 flying hours on the airframe.

In 1946, the JRS-1 was pulled out of storage and modified for a unique role. The airplane was part of a research project conducted by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the predecessor to NASA. NACA used the JRS-1 in a series of experiments to improve the hull designs of amphibious aircraft and seaplanes. When the experiments concluded, the JRS-1 was sent to Bush Field in Georgia for long-term storage.

When the JRS-1 was in storage at Bush Field, a ferry pilot curious about the airplane began flipping through the airplane’s logbook, which documented the JRS-1’s flights and history. While looking through these entries, an entry dated December 7, 1941, caught the pilot’s eye. At the time, the Smithsonian Institution was in search of an aircraft for its collection that had been at Pearl Harbor during the Japanese attack. After seeing the logbook, the pilot contacted the U.S. Navy, who promptly contacted the Smithsonian Institution and asked them if they would like the JRS-1 for the National Air and Space Museum. After several discussions, the U.S. Navy agreed to donate the JRS-1 to the Smithsonian Institution, and the National Air and Space Museum took possession of the JRS-1 in 1960.

For many years, the JRS-1 sat in storage at the National Air and Space Museum’s Paul E. Garber Restoration Facility in Suitland, Maryland. Unfortunately, due to its size and limited space in the facility, the JRS-1 spent considerable time in outside storage, where the elements took their toll on the airframe. The current condition of the JRS-1’s airframe reflects those years of outside storage and damage sustained when the airplane was moved several times while in storage. The JRS-1 was eventually moved inside one of the buildings at the Paul E. Garber Restoration Facility, but could only be seen by visitors who signed up for curator-guided tours of the facility.

When the larger National Air and Space Museum Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center was built in 2003, museum curators planned to move the JRS-1 into the newer building, which could accommodate larger aircraft on display that the flagship building on the National Mall could not. Unfortunately, due to a lack of funding, the planned restoration hangar for the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center was not built as part of the initial museum project. In 2008, the National Air and Space Museum finally raised enough funding to complete the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar portion of the Steven F. Udvar Hazy Center. This state-of-the-art restoration facility was completed in 2010.

In March 2011, National Air and Space Museum curators moved the Sikorsky JRS-1 to the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar. The aircraft was put on several flatbed tractor-trailers in pieces for the trip from the Paul E. Garber Restoration Facility in Maryland to the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia. Once in the hangar, museum curators began working on the preservation and conservation of some airframe components to repair corrosion and prevent further damage. The move from the Paul Garber Restoration Facility to the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar also allowed the JRS-1 to be stored in an environment with improved climate control to prevent further deterioration of the airframe. Some components, such as the tires for the main landing gear, were dry-rotted beyond salvage and needed to be replaced with new examples.

During its time in the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar, the JRS-1 was visited by Lt. Cmdr. Harvey Waldron, U.S. Navy (ret.), who flew on the aircraft as the radio operator during several patrol flights after the Japanese attack. Waldron was just going off duty when the Japanese attacked on December 7, but by December 8, he was flying on patrol missions as a radio operator in the museum’s JRS-1. Waldron could hardly contain his tears as he saw the JRS-1 and his old radio operator’s position for the first time in nearly six decades. In addition to visiting with his old airplane, Waldron agreed to give a three-hour oral history of his experiences during the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor to the National Air and Space Museum. Waldron passed away in 2017.

The pilot of the National Air and Space Museum’s JRS-1 during the flight to search for the Japanese fleet on December 7, 1941, Ensign Wesley Hoyt Ruth, also gave several interviews about his experiences, which were also the subject of a book about the attack. Ruth and the other pilots who flew the JRS-1s that day on the search mission to locate the Japanese fleet were awarded the Navy Cross for their efforts. Surviving the war, Ruth had a long career in the U.S. Navy, retiring in 1960. The decorated Pearl Harbor veteran died in 2015 at the age of 101.

After spending several years in the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar, museum curators decided to assemble the JRS-1 in its unrestored condition and display it on the museum floor of the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. Moving the JRS-1 out to the museum floor allowed the millions of visitors the museum welcomes annually to see the aircraft up close. It also freed up space in the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar for several restoration projects National Air and Space Museum curators had planned for the years ahead. At this time, museum curators have not decided if the JRS-1 will be restored to its colorful inter-war color scheme or the blue-gray scheme it wore after the Pearl Harbor attack. As the National Air and Space Museum is currently completing a major renovation of the flagship building on the National Mall, the complete restoration of the JRS-1 is likely several years away.

Today, the Sikorsky JRS-1, in its current condition, has many stories to tell visitors of the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. People seeing the JRS-1 for the first time wonder what an airplane in such bad shape is doing in a museum. After reading the information placard nearby, members of the public realize the JRS-1’s importance in the museum collection.

The blue paint, hastily applied in the weeks following the Pearl Harbor attack, has faded over time due to outdoor exposure to the elements. Today, the strokes made by the ground crew member who sprayed the JRS-1 blue-gray are visible on the airframe. The uneven nature of the strokes and their inconsistent lengths give clues to how quickly the paint job was done. The fading paint has also revealed that this paint was applied over the JRS-1’s original bright yellow and silver paint scheme. Visible through the paint are the JRS-1’s identification stripe and VJ-1’s squadron emblem, which was a pelican with a photographer in its beak carrying mailbags. This emblem is a nod to VJ-1’s original mission of utility work, such as transporting mail, personnel, and cargo to various military installations throughout the Hawaiian Islands.

Visitors to the museum can also examine the interesting features of the Sikorsky JRS-1, including the engines mounted up high on its wing and the conventional main landing gear wheels that retract into the streamlined hull. The JRS-1 also exhibits signs of exposure to the elements, which came from spending many years in outdoor storage. Torn fabric, shattered fuselage windows, and missing access panels are all visible on the JRS-1. Fortunately, enough of the original airframe remains intact so it can be fully restored to its original condition in the future.

The Sikorsky JRS-1 in the National Air and Space Museum collection is one of fewer than ten aircraft surviving that were present during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The JRS-1 holds the distinction of being the only aircraft in the National Air and Space Museum’s collection that was at Pearl Harbor that day. Sent out after the attack to search for the Japanese fleet, this JRS-1, usually used for utility and aerial photography work, was pressed into service for a mission it was never intended to do. On December 7, 1941, despite the enormous risk to themselves if they had been discovered by Japanese fighters, the crew of this JRS-1 and the others assigned to search for the Japanese fleet in the hours after the attack performed their mission with the utmost professionalism and dedication. In the weeks following the attack, this aircraft and the crews that flew it performed invaluable service by providing aerial photos for damage assessments and salvage operations.

Today, as museum visitors walk past the Sikorsky JRS-1 in the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, they may see it as a rundown, old airplane. Those who know its story or stop to read the information placard realize they are looking at an aircraft that witnessed history, as it happened. The Sikorsky JRS-1 is an important reminder to all Americans to always remember what took place at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the men and women who made the ultimate sacrifice in service to our nation on one of the darkest days in American history.